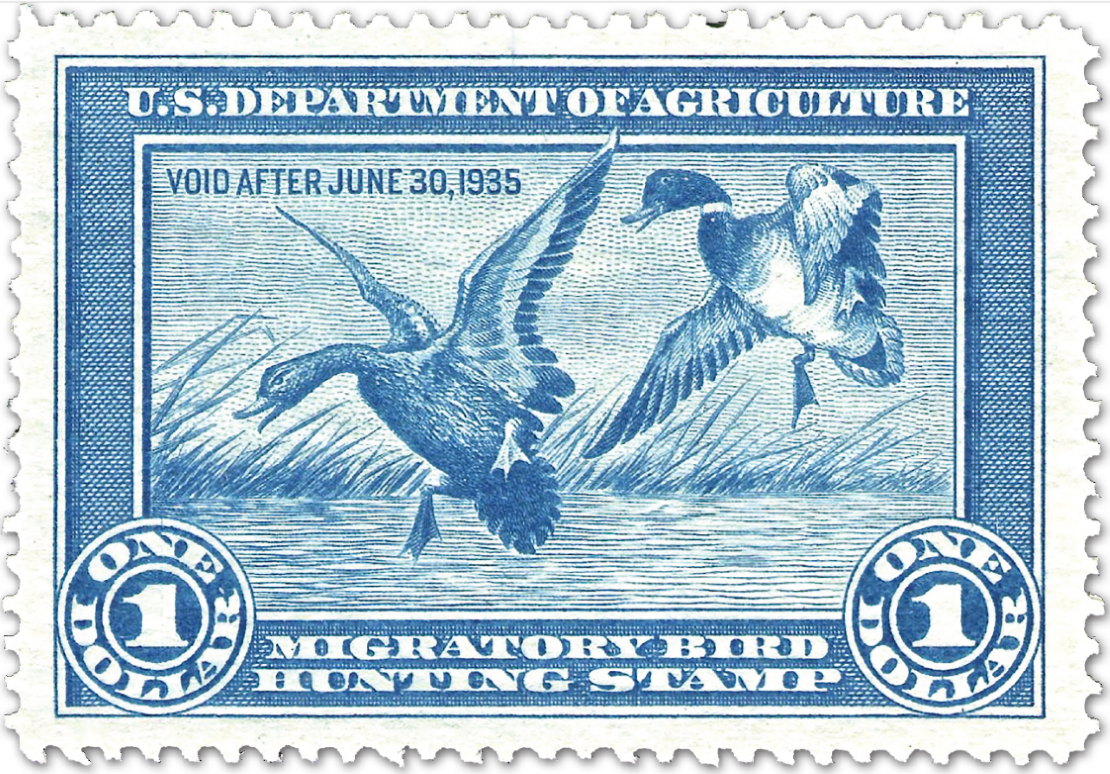

This artwork by famed cartoonist and noted conservationist Jay N. “Ding” Darling graced the first Federal Duck Stamp in 1934. Darling was the chief of the Biological Survey, a precursor of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, from 1934-36.

Fair to Fowl

Conservationist Ray P. Holland, Class of 1904, was a fierce advocate for migratory birds and the force behind the Postal Service’s still popular duck stamp.

In his 1946 book Now Listen, Warden, the Class of 1904’s Ray P. Holland related this paraphrased anecdote:

A United States Game Warden is journeying by train through the American Midwest during the 1920s. He sits next to a traveling salesman and strikes up a conversation without ever properly introducing himself. The salesman is a skilled talker and lightly touches upon several polite topics including sporting life. In turn, the warden asks the salesman if he’s ever hunted duck. The salesman replies that he just had a marvelous weekend mallard shooting in the town adjacent to the train’s original station. The warden then introduces himself and relays that it’s not duck season and hunting is illegal this time of year. The warden then asks for the salesman’s name. The salesman responds, “I’m the biggest damn liar this side of the Mississippi!”

Raymond Prunty Holland collected and documented dozens of tales similar to this during his career as both a district inspector and U.S. game warden for the Midwest and the editor of Field & Stream magazine. Although many of Holland’s stories are humorous, they record the reality of enforcing early wildlife conservation and management laws. Like his contemporary, Aldo Leopold, Class of 1905, Holland’s lifelong interest in hunting, fishing, camping, and hiking led him into an occupation that was just taking shape within the country. But unlike Leopold, Holland’s impact on the field is often overlooked despite his fervent advocacy for migratory birds.

By the time he became a U.S game warden in 1914, Holland was already an established freelance writer and photographer stationed in his hometown of Atchison, Kansas, nestled alongside the Missouri River. In fact, Holland began freelancing by submitting a paper he wrote as a Lawrenceville student to Sports Afield magazine. His flexible schedule allowed Holland to trek through the wilderness and engage in sporting life, which was the overarching subject for all of his written pieces. He quickly observed, however, that both “game hogs” and “market hunters” were rapidly depleting waterfowl populations through mass slaughter. At first, Holland drafted articles urging sportsmen to try “his way of spring shooting,” which eschewed riflery and supported the use of Kodak cameras to capture images of waterfowl. But when the Migratory Bird Protection Act of 1913 was passed by Congress, Holland began to lobby congressmen via telegram to support appropriations to enforce the law.

As a U.S. game warden, Holland took a holistic approach to enforcing wildlife conservation and management laws within his assigned Midwestern territory, publishing articles and humorous tales to advocate for game and presenting lectures to hunting clubs.

As he spoke for the rights of migratory birds and other local fauna, the constitutionality of the Protection Act of 1913 was being questioned by numerous Midwestern states, many of which argued the Constitution’s Commerce Clause was not a valid foundation for national waterfowl regulations. To combat this notion, an international treaty with Canada was proposed and implemented as the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. A year later, Holland was forced to legally test the constitutional power and extent of the treaty.

During the spring of 1919, Holland arrested several men — including the state attorney general of Missouri, Frank W. McAllister — for hunting ducks in the offseason. Although McAllister initially tried to retaliate during his arraignment by having Holland arrested for possessing wild ducks without a state hunting license — a charge eventually dropped — the state of Missouri ultimately claimed that Holland’s arrests were unconstitutional. The treaty was upheld in the lower courts but Missouri appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. On April 20, 1920, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Holland in Missouri v. Holland. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.’s statement identified the constitutionality of both the Migratory Bird Protection Act of 1913 and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. It was also determined by the court that migratory birds do not claim permanent homes within a state’s boundaries and are therefore not property of the state. The ruling was an achievement for the wildlife conservation movement and for Holland’s career.

At first, Holland drafted articles urging sportsmen to try ‘his way of spring shooting,’ which eschewed riflery and supported the use of Kodak cameras to capture images of waterfowl.

Three months after the Supreme Court ruling, Holland published an article in the July 1920 issue of Field & Stream magazine proposing the creation of a fifty-cent “duck stamp” attached to hunting licenses that would allow the licensee to shoot migratory waterfowl. In essence, the stamp would act as a federal hunting permit issued by the Department of Agriculture that would generate revenue to fund migratory bird refuges.

By 1922, the “duck stamp” initiative was backed by Dr. Edward H. Nelson of the U.S. Biological Survey (the precursor to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) and proposed to Congress as “The Public Shooting Grounds Bill.” Widespread opposition to the bill — including from Aldo Leopold — claimed the proposed refuges would become federally operated hunting grounds that would not foster the population growth of migratory birds.

Congress vetoed the bill, but Holland and his colleagues would persevere. Holland became editor of Field & Stream magazine in 1924 and used his position to continue his advocacy for waterfowl, but it was the Dust Bowl that helped prompt the creation of the Duck Stamp Act in 1934. Droughts in the American Midwest caused migratory bird breeding grounds to dissipate, but hunters continued to massacre fowl, decimating the population and forcing federal intervention. Holland’s vision for migratory waterfowl came to fruition fourteen years after he began campaigning for its creation.

After resigning from Field & Stream in 1941, Holland drafted numerous articles during the postwar period for popular publications such as The Saturday Evening Post and Collier’s, and published several books. Holland helped to revitalize the American Game Protective Association after thirty years of dormancy in 1958 and, as its president, helped to establish game refuges throughout the Midwest during the 1960s. Holland leaves a legacy of wildlife advocacy that few can rival but all can be inspired to achieve.

* * *

Sarah Mezzino is the curator of decorative arts and design for The Stephan Archives. This article was inspired by research conducted for the exhibit “Canceled Culture: First Day Covers and Historic American Stamps,” on display in Bunn Library through 2026.