Saving Sequoia

Michael Cantor ’79 is returning the century-old ‘Floating White House’ to its grandeur of long ago, creating a mobile museum of presidential history.

Some forty years after the Brooklyn Bridge was completed in 1883, transforming John A. Roebling’s signature design into a national icon, his granddaughter, Emily Roebling Cadwalader, commissioned what would become another key article of American history. Over the next half-century, her opulent 104-foot wooden yacht would play both elegant host and silent witness to some of the 20th century’s most significant moments of international strategic planning and diplomacy, as well as the notable celebrations and heartbreaks of the ten U.S. presidents who found a comfortable retreat aboard Sequoia – the floating White House.

Today, the 99-year-old Sequoia sits in Cambridge, Maryland, on the state’s Eastern Shore at the Richardson Maritime Museum, awaiting a long-overdue restoration. Michael Cantor ’79, managing partner of Equator Capital Group, the private-equity firm that owns Sequoia, has undertaken the job of restoring the craft to its 1930s grandeur, echoing a time when Franklin D. Roosevelt GP’57 cruised thirty-nine times aboard the craft. For Cantor, the project allows his interest in the past and enthusiasm for wooden yachts to dovetail in a meaningful way.

“I did grow up around water, and with boats. And I worked at construction during my summers at Lawrenceville back in Kentucky, doing carpentry,” he says. “I never had a nice wood boat, though.”

“But … this was an accident,” he says of taking on the Sequoia project. “I didn’t set out to do this.”

Cantor and Equator Capital were awarded ownership of Sequoia by a Delaware court in 2016 for a price officially recorded as “zero dollars,” but only after Equator, as mortgage holder, had paid out some $7 million to the previous owner, and in attorneys’ costs.

“After loaning him enough to pay off his previous mortgage, we had to pay to maintain the boat, pay his insurance maintenance and everything that he wasn’t doing, and then we had to pay all these legal fees,” Cantor says. “And the frustrating part was that none of that went to help Sequoia.”

The yacht’s condition would have appalled any of the commanders-in-chief who used it for state business, from Herbert Hoover GP’58 ’59 to Gerald Ford. It was, according to the chancery judge, Sam Glasscock III, “an elderly and vulnerable wooden yacht … sitting on an inadequate cradle on an undersized marine railway in a moribund boatyard on the western shore of the Chesapeake, deteriorating and, lately, home to raccoons.”

Last October, after four mostly idle years in Belfast, Maine, Sequoia was transported back to Cambridge, where the restoration — expected to take as long as five years, under the work of up to twenty shipwrights – could cost $10 million.

Sequoia was designed by John Trumpy and constructed by the Mathis Yacht Building Co. of Camden, New Jersey, in 1925 for Emily Roebling Cadwalader and her husband, Philadelphia banker Richard M. Cadwalader, who paid $200,000 – the equivalent of $3.5 million today. Built of longleaf yellow pine, white oak, mahogany, and teak, the yacht was launched that October as the Sequoia II, replacing the 85-foot Sequoia the Cadwaladers had purchased just one year earlier. The new wooden craft was used by the couple for several elegant cruises off Miami and West Palm Beach, Florida, which were noted in the local society pages; in the summer, they cruised the Delaware and Chesapeake bays.

Seeking to impress Richard’s fellow members in the New York Yacht Club, Emily Cadwalader’s attention again began to stray toward a larger vessel, and so the Sequoia II was sold to Houston oil magnate William Dunning in 1928. Dunning’s fortunes plunged during the Great Depression, and he was forced to unload Sequoia II in 1931, when it was purchased by the U.S. Department of Commerce for $40,000. The serial designation was dropped from its name, and Sequoia was used for two years as a decoy to lure bootleggers, who were fooled by the craft’s lavish appearance, on the Chesapeake and Delaware bays, according to the yacht’s longtime captain, Giles M. Kelly, in his book, Sequoia: Presidential Yacht.

Hoover’s use of Sequoia for both official and personal use marked the beginning of the long and integral relationship between the yacht and the presidency.

Hoover, an admirer of Mathis-Trumpy yachts, also began using Sequoia in 1931. He grew so fond of the craft that its photo graced the 1932 White House Christmas card. Though he was criticized for showcasing such opulence while Americans were enduring unprecedented economic hardship, Hoover’s use of Sequoia for both official and personal use marked the beginning of the long and integral relationship between the yacht and the presidency.

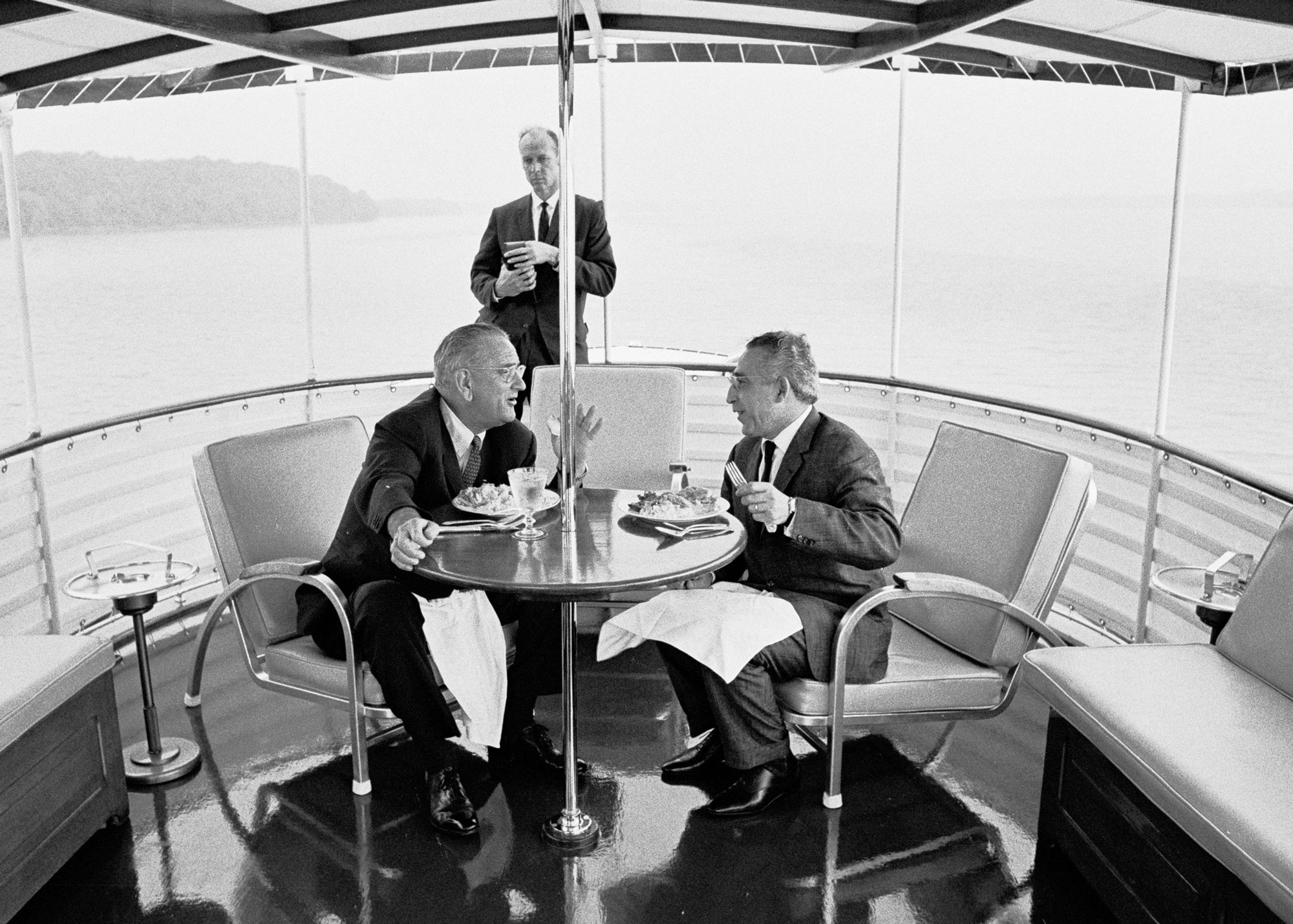

Three months after the United States detonated atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, President Harry S. Truman hosted Prime Ministers Clement Attlee of Great Britain and William Lyon Mackenzie King of Canada on a cruise past Mount Vernon to discuss the control of such weapons. The next year, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower and British Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery conceptualized what would become NATO aboard the yacht. During the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, President John F. Kennedy held secret talks on Sequoia; seven months later, he celebrated his 46th and final birthday on board. Richard M. Nixon reached his decision to resign the presidency in 1974 while aboard Sequoia, wistfully rendering “God Bless America” on the yacht’s piano in the aftermath of his choice. Designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1987, Sequoia had passed through a series of private ownerships after being sold by President Jimmy Carter in 1977. Cantor took ownership in 2016 and possession in 2019 following litigation with the Virginia shipyard that had damaged Sequoia’s hull.

“Have you ever heard of Theseus’ paradox?” Cantor asks. It’s a philosophy exercise that raises the question of whether an object — say, a wooden yacht badly in need of restoration — that has had all of its components replaced is fundamentally the same object.

“In Maine, they express it in a different way,” Cantor explains. “They say, ‘This is my grandfather’s axe. He loved this axe. He put two new heads and three new shafts on it.’ And then you think to yourself, Well then, is that really his axe?”

I’m a conservationist, so even if someone will let me, I’m not going to go cut down a 400-year-old tree and use it for this.

It’s a question Cantor has found himself considering as he searches for the wood to replace Sequoia’s hull. The planking on the outside of the hull was originally longleaf yellow pine and the framing, white oak. Cantor is insistent these elements be used in the restoration, but not just any longleaf yellow pine or oak will do.

“There were 90 million acres of old-growth, longleaf yellow pine in the southeast when Columbus landed; now there are around 9,000 acres,” he explains of the endangered species. “And I’m a conservationist, so even if someone will let me, I’m not going to go cut down a 400-year-old tree and use it for this.”

Cantor recalls a conversation with Todd French of French & Webb, the Belfast, Maine-based firm tapped to do the restoration, about procuring wood for the job. Explaining his requirements, Cantor said, “We have to find old-growth white oak and longleaf yellow pine that has fallen naturally and shares the presidential history,’” he recalls. By “presidential history,” Cantor means sourcing wood from properties with direct links to the U.S. presidents who have cruised aboard Sequoia – a task taller than even the trees themselves.

“And Todd’s like, ‘Are you effing crazy?’” he says. “But we did, at least for all the longleaf yellow pine.”

Adding degrees of difficulty to their search is that if a tree is snapped by strong winds, the breakage weakens the structural integrity of the wood, rendering it unusable. For Cantor’s purposes, he is seeking timber from trees that toppled at the roots due to the destabilizing combination of heavy rains and high winds. Keeping his ear to the ground, he tapped into what he calls a fanatical subculture of people who deal in wood for historic yachts.

“And one of them told me about this plantation in Georgia where Hurricanes Irma and Michael had knocked down 150 old-growth trees,” he says. The property, Cantor explains, was formerly owned by John Hay “Jock” Whitney, Eisenhower’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s. Whitney was the second husband of Betsy Cushing Roosevelt Whitney, who had been married in the 1930s to James Roosevelt II, son of the president. The link to F.D.R. was already in place, but Cantor found something that strengthened it – old film, donated to the Roosevelt Library in 2018, that once belonged to Marguerite “Missy” LeHand, the president’s longtime private secretary, depicting Betsy Cushing Roosevelt and the president aboard Sequoia during her marriage to James.

The longleaf yellow pine to be used comes from this land, says Cantor, who is also gratified that the wood will have strong bipartisan credentials. He underscores the connection to Roosevelt, a Democrat, but adds that Jock Whitney and public relations practitioner “Tex” McCrary were the forces behind the famous 1952 rally at Madison Square Garden to persuade a skeptical Eisenhower to run for president as a Republican. Eisenhower, who would suffer a heart attack during his first term, “supposedly made the decision [to run for reelection] while bird hunting on this plantation,” Cantor says.

Even the nation’s most esteemed independent — George Washington — will be represented in the restoration of Sequoia, whose link to the first president’s Mount Vernon estate is strong, according to Cantor.

“In 2019, I read that the last white oak personally planted by Washington fell,” he says. “So, I need white oak, and I called the arborist and he said, ‘No, you can’t have it.’” But after negotiation, Mount Vernon generously donated the wood to the Sequoia project with a ceremony befitting the occasion.

Given its historical significance, it’s appropriate that the fully restored Sequoia will not only be used by Cantor but also function as an educational platform for the public.

Throughout its history, Sequoia was changed and adapted for the times and the users. Roosevelt’s elevator was converted into a bar by Lyndon Johnson, for example, all of which poses another question for Cantor: To which moment in time should Sequoia be restored?

“I’m definitely going to keep the bar, but try to pick a period during Roosevelt,” he says, adding that the 1960s saw such modifications as air-conditioning units punched through the mahogany walls. “We’ll pick a point when it was still a beautiful, classic yacht, before it got added onto.”

In October 2019, Michael Cantor ’79 had the decrepit Sequoia transported by barge to a shipyard in Belfast, Maine, to begin restoration back to its Roosevelt-era appearance.

When the restoration is complete, Cantor will oversee an artifact of U.S. history that was the envy of even the nation’s global adversaries – some of whom later became friends. When Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev visited Washington, D.C., in 2001, he was photographed with his daughter, Irina Virganskaya, and then-captain Tony Wells aboard Sequoia. “When ‘Gorby’ came up to the wheelhouse,” Wells told a reporter, “he grasped the steering wheel and declared, ‘Now, at last, I am in charge of America’s Ship of State.’”

Given its historical significance, it’s appropriate that the fully restored Sequoia will not only be used by Cantor but also function as an educational platform for the public.“She will cruise locally and along the East Coast,” Cantor says, “as a floating venue to teach American presidential history and to promote conservation and ocean conservation causes.”