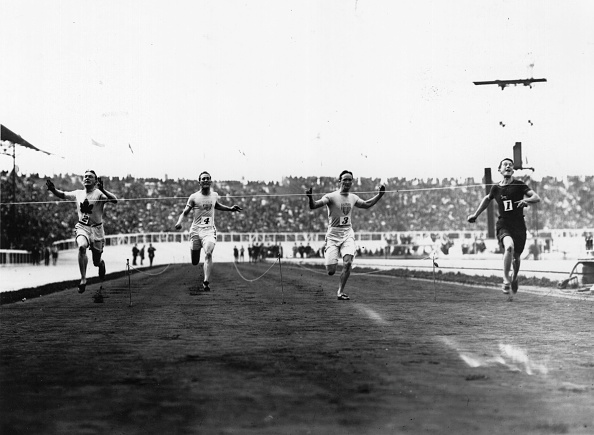

James A. Rector, second from right, finished to South Africa’s Reggie Walker (right) by a tenth of a second in the 100m final at the 1908 London Olympics.

Lawrenceville’s Summer Olympians: James Alcorn Rector, Class of 1906

James A. Rector entered the 1908 London Olympics poised to win his event in the eyes of many. Touted as “America’s Greatest Amateur Sprinter,” he had the record to back the claim, but Rector's noble sense of sportsmanship would be his undoing in the final.

James Alcorn Rector entered the 1908 London Olympics poised to win his event in the eyes of many. Touted as “America’s Greatest Amateur Sprinter,” Rector had the record to back the claim. The Hot Springs, Arkansas, native was a fine three-sport athlete who also excelled in the classroom as the valedictorian of the Class of 1906. But Rector’s greatest reputation was earned on the track, where he particularly excelled in the 220- and 100-yard dashes. According to The Lawrenceville Alumni Bulletin of October 1, 1914, Rector only lost two races in his life: once to Kingsley Swan, Class of 1908, who ran the 100 in 10 ⅖ seconds (times were measured to the closest 1/5 of a second), and again in his very last competition in the Olympic games.

Rector, who left Lawrenceville in possession of two school records – 10 seconds in the 100, and 22 seconds in the 220 – was elected captain of the track squad at the University of Virginia, and soon began to rewrite the Cavaliers’ record books, as well. The freshman set new school marks in the 100 and 220 in his very first meet in 1907, and by the next year, after abandoning the 220 to concentrate on the 100, he ran a record 9 ⅗ against Johns Hopkins.

In June 1908, the speedy Rector qualified for the London games by tying an Olympic record of 10 ⅘ seconds in the 100 meters (the standard length for international and Olympic competition; yards were still used the United States.) in Philadelphia. Later that month, he sailed for England as the favorite in the 100 meters. As reported by the Bulletin, Rector had only been there for a matter of hours when he was approached by a man from South Africa, who said he was training a runner who would compete against him.

“He told me that the youngster under his charge knew little about the game, but had the native ability to become a great runner,” Rector told the Bulletin. “He complained that his starting was bad and asked me to lend a helping hand. I agreed.”

Rector’s noble sense of sportsmanship would be his undoing. The South African trainer introduced him to Reggie Walker, who watched Rector closely, mimicking his starting method. Rector did not see Walker again until the next day during warmups for their race. When he did, he noticed that Walker had mastered his starting technique.

In semifinal heats that day, both Rector and Walker equaled the existing Olympic record of 10.8 seconds (adjusted for modern timekeeping), but in the final, Walker again ran a 10.8, crossing the finish line a half yard ahead of Rector, who was credited with a 10.9.

“When the race was on, he got away from the mark ahead of me,” Rector continued. “It was the first time I hadn’t shaded my competitors from the start. We ran neck-and-neck and he beat me by inches.”

It would be the last time Rector ever donned racing spikes in a formal competition. Retiring to concentrate on his studies, Rector earned a degree in law in 1909. He joined the firm of Taliaferro, Rector and Taliaferro in St. Louis, where he practiced for more than thirty years before returning to Hot Springs. After retiring in 1943, Rector devoted himself to oversight of the Rector Family Trust until his death in 1950.

A version of this story appeared in the summer 2016 issue of The Lawrentian.