A Just Legacy

Lawrenceville’s first Black student council president ponders the U.S. Supreme Court’s dismantling of college legacy admissions just as his family gained an institutional foothold. Is it for the best? Does it even matter?

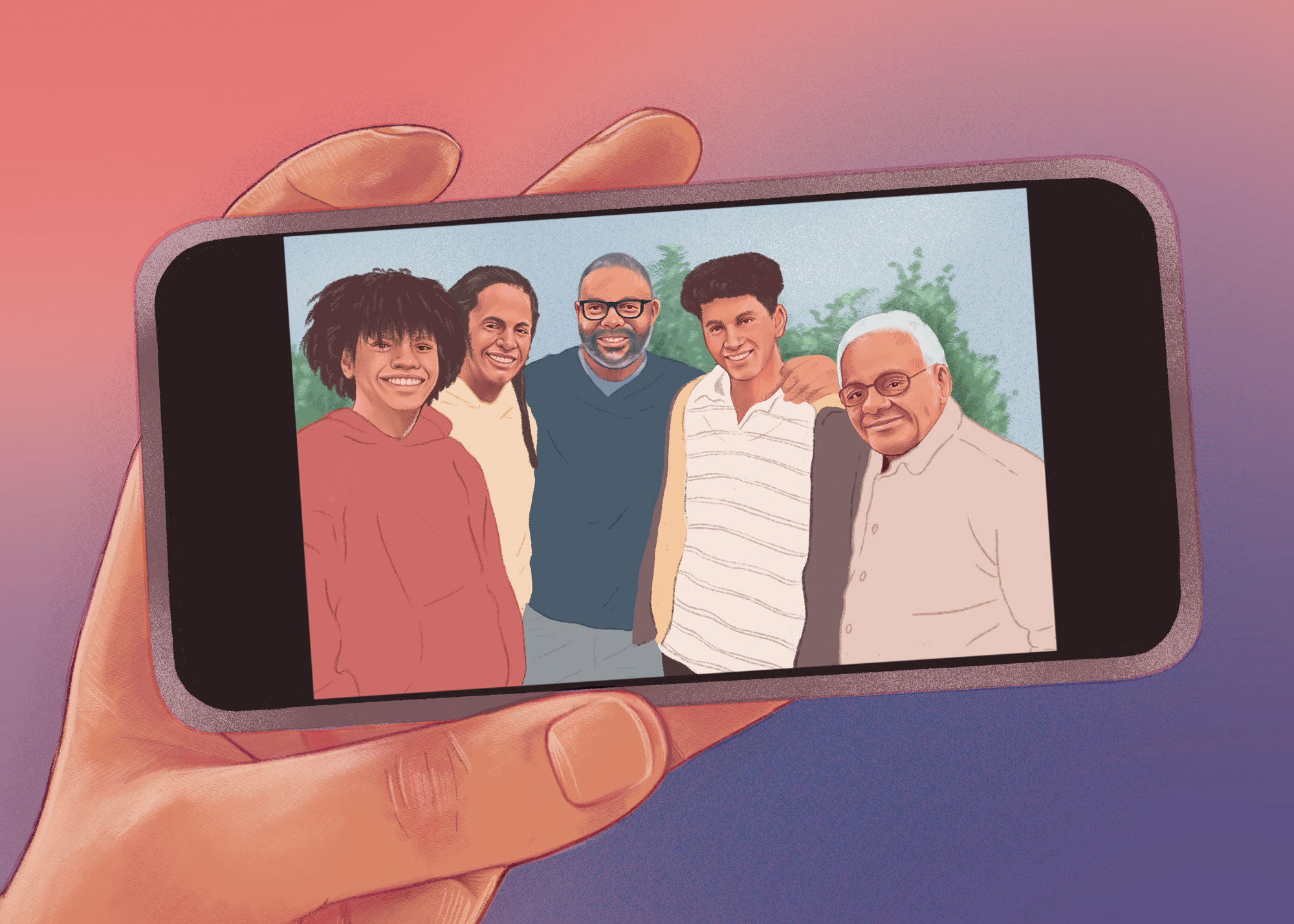

A casual swipe through my phone will bring you to a photo that features my uncle, my two sons, my cousin, and me, posing on a backyard porch. It’s an informal shot, undistinguished from dozens of others you’ll find in my albums, if not for something rare that is documented by it: three generations of Black Lawrenceville students and faculty from one family.

When I walked the Lawrenceville campus more than 40 years ago as a student — a wispy teenager with a colossal ’fro — family legacies were not only common, but seemingly the birthright of the overwhelmingly white student body. Legacy admissions — the practice of assigning value to a student application based on family history at an institution — was an enduring symbol of Lawrenceville’s exclusive race and class history.

But my own family’s journey demonstrates just how precarious a multigenerational Black presence at Lawrenceville can be. Lawrenceville was more than one hundred fifty years old before it accepted its first Black student and faculty member. Max Maxwell H’72 ’74 ’79 ’80 ’81 ’88 ’91 ’93 ’00 ’01, my uncle, was the only Black teacher for more than a decade after arriving in 1969, and without him, I would never have known about Lawrenceville. Even after I was accepted to Lawrenceville, I almost didn’t matriculate when I discovered I had passed the test for a specialized high school in New York. Both my sons have been students at Lawrenceville, four years apart, but neither was initially accepted into the school.

And this doesn’t even account for the brilliant women in my family who never even had the opportunity to apply to Lawrenceville prior to 1987.

The fact is, other than historically Black colleges and universities, precious little Black history has been recorded at private educational institutions, so it’s no surprise that the idea of self-perpetuating White Anglo-Saxon Protestant bloodlines at elite colleges is both persistent and under fire. In the last ten years, according to The Chronicle of Higher Education, more than a hundred colleges and universities have dropped legacy admissions practices, including Amherst, Johns Hopkins, and Wesleyan. And now, In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent dismantling of college affirmative action, legacy admissions are receiving renewed scrutiny and public backlash. Harvard, the canary in the coal mine, is, at the time of this writing, being sued while undergoing an investigation by the Biden administration for its legacy admissions policies. Meanwhile, educators, policy makers and op-ed writers alike are asking: What kind of admissions policy befits a multiracial and egalitarian nation? How do any of us, over generations, gain equal access to opportunities and quality education? And what does race, if anything, have to do with it?

I couldn’t help thinking that legacy admissions had benefited white folks since time immemorial, but the drawbridge was being raised just as my tribe approached the ivory tower. On the other hand, I instinctively resist the idea of rewarding even a ration of social advantage and educational privilege with more advantage and privilege.

These are good questions, not just for colleges, but for competitive independent schools to consider as well. But while ending legacy admissions may seem like a no-brainer, the headline of an August 2023 opinion piece in The Atlantic by Xochitl Gonzalez captured just how complicated the matter can be when applied to people who have barely gained a foothold in American mainstream institutional life: “Legacy for you, but Not for Me – Hate the establishment if you want to. But don’t get rid of it the minute that Black and Latino people become members.”

Indeed, at the time when my children were initially denied admission to Lawrenceville – one was waitlisted and eventually admitted later in the year; the other had to apply a second time before being accepted – I couldn’t help thinking that legacy admissions had benefited white folks since time immemorial, but the drawbridge was being raised just as my tribe approached the ivory tower. On the other hand, I instinctively resist the idea of rewarding even a ration of social advantage and educational privilege with more advantage and privilege.

As it turns out, although Lawrenceville does recognize legacy, the privilege afforded those students may be less than you may imagine. “We are past the point where you can just sail in as a legacy,” says Kyla Kupferstein Torres, a Black educational consultant whose roles over the past 20 years have included being a director of admissions at both the Oliver Program and the Hunter College High School. “Those days have been over for some time.”

Greg Buckles, the Shelby M.C. Davis ’54 Dean of Enrollment Management at Lawrenceville, puts a finer point on it. “We still put a thumb on the scale for legacies, but they have to be fully qualified,” he says. Buckles went on to describe a rating system that the admissions readers use during the decision-making process at Lawrenceville: Out of a possible total of 25, academics can count for up to 10 points; testing, 5 points; 5 points for personal qualities, which includes an observation from an admissions interview; and a possible 5 points for extracurricular activities. The average score for legacy admits is 17.5, which is the same for the overall number of students admitted.

According to Buckles, legacy is not part of the formal admission criteria, but instead one of 26 applicant categorizations that also include gender, race, form, athletics, boarding/day, children of faculty/staff, etc. This rubric is used to help ensure a balance across a range of student characteristics. In the end, the admit rate for legacy kids ranges between 45 to 50 percent, compared with anywhere from 15 to 18 percent for the pool at large.

“It makes sense,” Buckles explains, that legacy applicants are competitive in their own right. Legacy kids are more than likely to come from “families who put a high value on education, are going to invest in education, and grew up with good reading habits, encouragement, and a range of cultural experiences.” They are “on par with other admits, because the only thing tougher than not taking a legacy kid is taking one that’s going to fail.”

My uncle Max, a veritable institution at Lawrenceville, has spent more than fifty years of his life attempting to re-engineer Lawrenceville from a place where Black bodies were tolerated to a place where Black and Brown humanity could find belonging.

My Community

Most people are surprised to learn that I once vowed never to send my children to Lawrenceville. I’ve spent my entire adult life working among low- and moderate-income Black folks in Central Brooklyn. I come from a family of New York City public school educators, and as a community organizer and journalist I’ve focused a big part of my career on supporting public schools. So even though I attended Lawrenceville myself, sending my children to a New Jersey private school seemed to be a betrayal of my social justice values and my commitment to the Central Brooklyn community.

But children – and for many, the often-stark limitations of a public-school education for Black children in New York City – have a way of bending our politics and expectations. And by the time my kids left primary school, I began to view Lawrenceville as not simply a school, but a special community, an ecosystem of supportive relationships and values where my children could flourish.

In fact, I was aware of these relationships and values because my family helped cultivate them.

My uncle Max, a veritable institution at Lawrenceville, has spent more than fifty years of his life attempting to re-engineer Lawrenceville from a place where Black bodies were tolerated to a place where Black and Brown humanity could find belonging. He and my aunt, Barbara, were advisers, den parents, and safe harbors to early generations of Black students who were often plucked haphazardly from urban environments and struggled, sometimes bitterly, to find comfort in a setting where they were aggressively marginalized. And in subsequent years, my aunt and uncle inspired a number of my cousins and friends to take a risk on the boarding experience at Lawrenceville as well.

My aunt and uncle laid fertile ground for me to become, among other things, the first Black student body president. But more important, soon after I graduated, I worked with Earl Wilson ’77 and Ralph Spooner ’75, and the dean of students at the time, Marty Doggett H’76 ’82 ’86 ’87 ’88 ’92 ’98 P’00, to orient incoming Black students. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s I co-organized the first Black alumni reunion, co-founded the predecessor to Lawrenceville’s current Black Alumni affinity group, spoke before numerous classroom, School and alumni assemblies, and served on Lawrenceville’s executive alumni committee. I was explicitly seeking to create a place where future generations of Black students could thrive, but subconsciously I was seeking a school I could entrust with my unborn children.

While at the Oliver Program, Kupferstein Torres was part of an apparatus that helped prepare Black, Brown and low- and moderate-income families to attend independent schools like Lawrenceville. She acknowledged the obvious — that admitting the children of alumni is a way of developing self-interested donors — but also noted that schools represent a “greater community.”

“Lawrenceville is not just students who attend now,” she says, “but students who attended in the past, people who become parents, people who become grandparents.” Legacy admits have been historically important because schools want to “flag an existing connection to the institution,” and legacy students become opportunities for schools to demonstrate “an awareness that they have about their surroundings and who is in their application pool.”

The question of legacy admission, and whether Black and Brown applicants are able to take advantage of it, speaks directly to the question of who gets chosen to be a living and active part of a school’s history and narrative. Heather Flewelling, a Black woman who attended St. Paul’s School in New Hampshire and for nineteen years counseled students at Milton Academy and helped Milton tackle institutional diversity questions, observed, “There are different vibes at different schools, and it takes a while to pass that culture along. And so, having some applicants and some students coming in that have heard a narrative, beyond their day-one, of those values and those traditions, helps the institution maintain some of that narrative.” Legacy kids, Flewelling points out, are the “cultural translators for their peers” who can tell the story of what the school “once was and, hopefully, how far it has come. Sometimes you need the narrative to carry backwards and say, yes you can, you can do this. And we are here and we’ve been here. And upon my shoulders you may stand.”

Academic institutions are inequitable walking in the door, because you can’t just say it’s based solely on academic achievement. You can’t just say you’re going to take the smartest kids. How are you going to measure that?

The Color of Equity

Lawrenceville is the perfect proving ground for issues such as race-conscious admissions, preferences given to athletes, and legacy. Unlike colleges and universities that accept federal dollars, Lawrenceville, and independent schools like it, are not subject to federal rulings. “We believe strongly in any independent school’s right to self-determination,” Buckles asserts.

But without any external pressures or formal guardrails for public accountability, this “self-determination” only increases the stakes for Lawrenceville to be more thoughtful in how it shapes its community. Meanwhile, calling the question of legacy forces us to confront some inconvenient truths.

“Is it ‘fair’? It’s useful, but of course it’s not ‘fair,’” Kupferstein says. “It’s insider trading, it’s compound interest. But an independent school is not a public school. It wasn’t established to offer an ‘equal’ shot.”

Flewelling takes it a step further. “Academic institutions are inequitable walking in the door, because you can’t just say it’s based solely on academic achievement. You can’t just say you’re going to take the smartest kids. How are you going to measure that?” she says. “How do you control for the educational, cultural, and environmental experiences that kids may or may not have had? How are you going to measure capacity to grow, capacity to achieve, and capacity to impact?”

At a time when the nation is so hopelessly divided into ideological camps, nuanced conversations about identity and community-building are hard to come by. Flewelling wonders whether we are free to consider “BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] legacy when the national discourse around privilege and access seems to suggest that we should get rid of” legacy all together. “We want to break down the institutional legacy of white and male supremacy AND we want to sustain a sense of who we were,” she says. “How do you do both?”

Paying Forward

Images from the morning of May 28, 2022, linger with me to this day. It was a moment of celebration and convergence for my family.

There was Max Maxwell, emotionally watching Manoc Joa-Griffith ’22 — my older son and Max’s late sister’s first grandchild — graduate as a member of the student council. Manoc had applied to Brown, my alma mater, but his legacy status had not moved the needle on his application. Instead, he was off to Cornell to study marine biology and run Division I track.

On stage at the ceremony was Manoc’s housemate, Andrew Boanoh ’23. When Manoc and Andrew were both part of Griswold House’s coterie of Black students a year earlier, Manoc regaled Andrew with stories of his Lawrenceville lineage. Now Andrew was on hand to accept the mantle of incoming student body president, as I had four decades ago.

And sitting next to me was my younger son, and Manoc’s little brother, Ayodele ’26, who weeks earlier learned he was moved off the waitlist and would attend Lawrenceville that September.

Of course, I was the only one who ascribed any significance to the confluence of these impressions. Few on campus are losing sleep over legacy admissions, a luxury concern to be sure. But Lawrenceville and its peers have only just begun to navigate the complexities of race and institution-building laid bare by it. And I’ll never know the impact that legacy — or the lack thereof — will ultimately have on Manoc and Dele on their educational journeys. What I am confident of is that along the way they have been loved, challenged, inspired, and well-resourced, which is another way of saying they have been privileged the way their ancestors dreamed they would be. In turn, I trust my children will do the same for generations to follow. I’ll sleep just fine knowing that.