By late 1961, science master Gifford Havens H’46 ’58 and his students were using the observatory they built.

Under the Stars

After years of obscurity, Lawrenceville’s astronomical observatory is being rediscovered by drivers arriving on campus through the new Gaw Entrance.

What is that peculiar building? With people now entering campus from Route 206 via the new Gaw Entrance, the white domed structure they pass on the winding access road is sparking a new level of curiosity now that it is again noticeable to an audience beyond golfers – or stargazers. Situated just north of the roadway, not far from the historic Old Brick faculty house, sits the School’s largely dormant astronomical observatory, once the place to look toward the heavens.

Though astronomy has been part of Lawrenceville’s science curriculum periodically since at least the 1830s, the study of the stars and planets has waxed and waned over the decades, depending on student interest and faculty expertise. The roots of the observatory, completed in 1961, might rest in the 1934 decision of science master Otto Rosner to introduce a new, weekly astronomy class. Using a 2½-inch aperture Ramsden telescope with a magnification of 75x, the class initially met on the lawn behind the brand-new Raymond House, but by spring 1935, their viewing location had moved to the golf course to take advantage of the dark skies unmarred by campus lights. By the following year, students were encouraged to look through the telescope before and after the regular Saturday night movie showings on campus to learn to track the movement of planetary bodies by comparing the before and after positions.

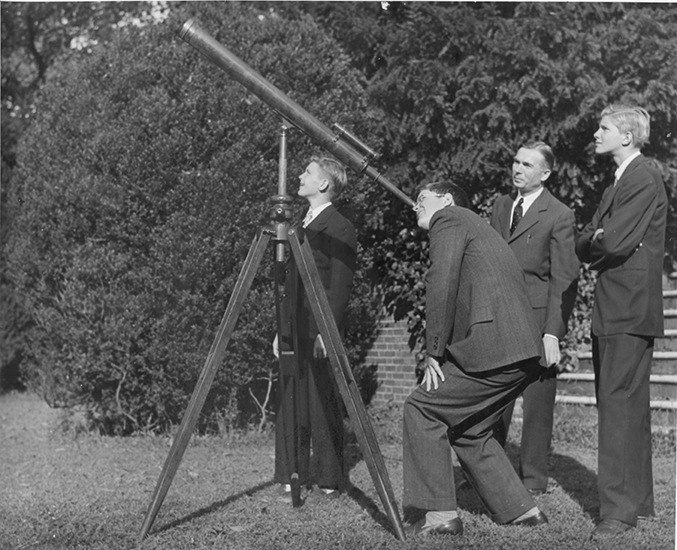

Students and science master Otto Rosner used a Ramsden telescope to see the stars from the Bowl in the 1930s.

One of the students inspired by Rosner’s class was Frederick Lum Ferris Jr. ’37 P’64 ’65, whose interest in astronomy had been spawned by the solar eclipse of 1932. By the time he began his Fifth Form year, Ferris had designed and built a homemade telescope in his family’s backyard in nearby Pennington. Having personally ground and polished the telescope’s reflective mirror, a critical part of the apparatus, Ferris reputedly used concrete and car parts to fashion a stable base for the device.

With an 8-inch mirror that brought the view of objects 400x closer, Ferris’s personal telescope was at the time the third-largest telescope in New Jersey, rivaling even those at local universities. After graduating from Lawrenceville, Ferris studied science at Princeton and Harvard before returning to teach science – including astronomy – at both Lawrenceville and Princeton from 1945-53. After joining Educational Testing Service in Princeton, Ferris would go on to develop science curriculums and testing for secondary education, and he even served on a panel of five scientists in the early 1960s that established the scientific qualifications for NASA astronauts to be considered “scientist-astronauts” in the Apollo missions.

When Ferris left Lawrenceville in 1953, he donated his large personal telescope to the School, but its size and the challenge of mounting and dismounting it made it impractical. In 1955, with the parabolic mirror for the Ferris telescope in hand, a newly formed Astronomy Club, under the guidance of science master Gifford Havens H’46 ’58, began planning for a redesigned telescope mounting and ways to make the device more usable.

One suggestion was to build an observatory at the viewing location on the golf course. By 1957-58, the Astronomy Club had built a mounting for the telescopic mirror, and in 1959, buoyed by a gift of $200 from the Fathers Association, Havens designed the observatory, using cinder blocks for the circular base and a steel grain silo dome for the roof. A 3-foot-6-inch viewing aperture that could be opened and closed was cut into the dome, while the entire roof could be rotated manually – using “student power” – on a metal track with eight wheels placed atop the cinder block wall. The ability to rotate the viewing aperture enabled stargazers to take in different areas of the sky while still being protected from the elements.

Students began working with Havens to build the observatory, and with help from members of the Astronomy Club and astronomy classes, it was completed in May 1961.

Over time, the use of the observatory became sporadic. While it has largely retained its original appearance, the environment around the structure had changed significantly. The intervening

sixty-plus years have brought a lush grove of trees just north of the structure, completely impeding the view of the night sky in that direction. Common astronomical practice dictates that a telescope must be oriented first to the North Star to follow the maps of the skies, but the obscured view now renders the observatory unusable for its original purpose. The ever-increasing issue of light pollution also hinders astronomical viewing from campus in general.

But with the building coming back into everyday view, it may be a matter of a few motivated stargazers and some simple landscaping – and a little stardust – to bring the observatory back to life.

* * *

Jacqueline Haun is the senior archives librarian of the Stephan Archives in Bunn Library.