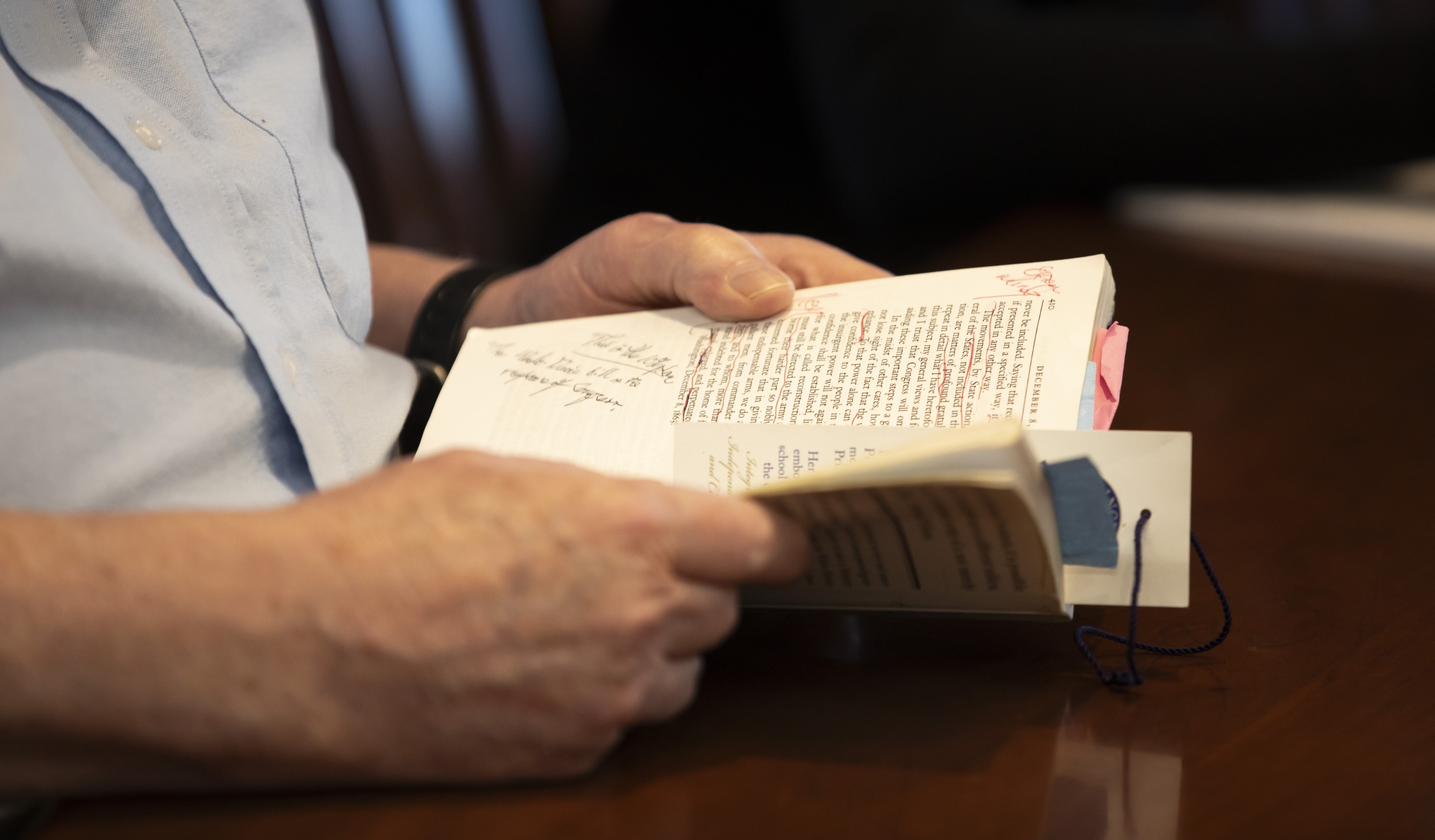

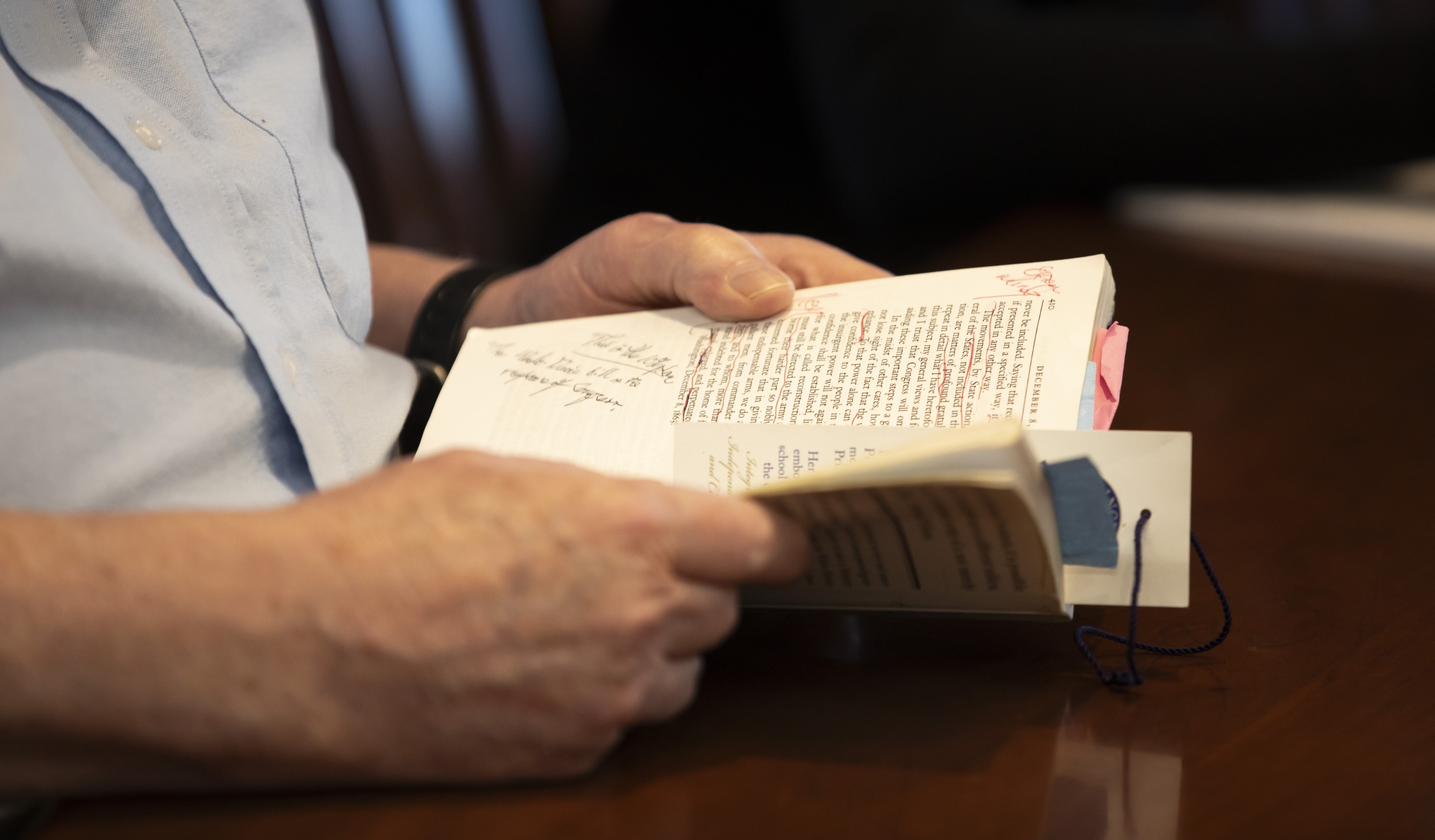

Underlined passages, notes scrawled in the margins, and tagged pages reflect history teacher Regan Kerney’s ever-expanding insights into the texts of Abraham Lincoln.

Unraveling Lincoln

America’s 16th president is a “mythological creature,” says history teacher Regan Kerney H’49 ’95 ’98 ’99 ’03 ’11, and it’s crucial for students to strip away the legend to uncover something real.

Three times a week each winter term, teacher Regan Kerney H’49 ’95 ’98 ’99 ’03 ’11 can be found in a corner classroom of the Noyes History Center, preparing for his succinctly titled course, Lincoln. With a well-worn copy of Abraham Lincoln: The Selected Speeches and Writings in hand, Kerney reviews the day’s syllabus for the course he has taught since 1998-99.

America’s 16th president, he explains, is a “mythological creature,” and it’s crucial for students to strip away the legend to uncover something real.

“You can have heroes,” Kerney explains, “but understand that heroes have flaws.”

The best way to do that? Examining Lincoln’s own words rather than relying on what has been said about him. Kerney’s text is filled with margin notes and Post-its as he leads students through Lincoln’s life, from his early letters to the Emancipation Proclamation, and from wartime correspondence with generals to letters written to everyday citizens.

Even with close readings, Kerney reminds young Lawrentians that parts of Lincoln will always remain unknowable.

“One of the dangerous tendencies we have is to fill in the gaps. Students have to be comfortable knowing there will be gaps in their knowledge,” he says. “Lincoln never sat down after the war to write his reflections […]. He never gave a lecture series on his experiences.”

Students are often surprised to see Lincoln as a work in progress over the three decades under examination. His capacity for change, Kerney says, is one of the most important takeaways from the class.

“Between 1858, when he debated Stephen Douglas, and 1865, when he was assassinated under the weight of the Civil War, he changed enormously,” Kerney says. “Not his personality, but his beliefs – particularly about race. He grew up a lot and kept changing. So, there’s hope for us all if you can still keep growing when you’re that old.”

Kerney revisits the entirety of Lincoln’s collected works every few years, his understanding deepening with each pass.

Students have to be comfortable knowing there will be gaps in their knowledge. Lincoln never sat down after the war to write his reflections.

“I sit down and read them again just to see if there’s something I missed. And every now and then, you find something really great in there,” he says. “But it takes time. Part of this for me is about how you teach a course. As my thinking keeps evolving, I’m trying to be like Lincoln. I’m trying to grow.”

Kerney hopes his students leave with a method of inquiry they can apply to any historical figure.

“I want them to know they can do this with anybody,” he says. “They can get into someone’s life and really know that person. This class is an example of how you would do it.”

Stripping the Myth from the Man

A close study of Lincoln helps students make sense of contemporary America.

“[In his 1855 letter to George Robertson, Lincoln] expresses a moment of pure human emotion that often isn’t discussed in talks of his legacy. This moment is when he confides in his friend that ‘the problem [of political division in the nation] is too mighty for me.’ This is not the competent optimist that many Americans think Lincoln was, but instead it shows his humanity, and that you may doubt yourself from time to time, but you can still harness your effort and bring great changes to the world if you are committed to the challenge.”

Tommy Morris ’25

“I don’t give you a lot to read. I give you things to read carefully. Read it slowly, savor it. Maybe read it twice. Because to be honest, it doesn’t make as much sense until you’ve read it about 20 times. You’d be amazed what happens the 20th time you read the Gettysburg Address.”

Regan Kerney H’49 ’95 ’98 ’99 ’03 ’11, history teacher

“[The course is especially relevant] because of the level of polarization we’ve reached in recent years. It’s important to study how political leaders in the past have handled a nation that is so divided. Lincoln talks a lot about the Constitution and is more concerned with upholding democracy than he is with power.”

Nell Bunn ’25